family matters

A friend and I were talking on a long car journey about space within the couple. He mentioned the phenomenon of The Thunderstorm and The Turtle and ever since then I have been observing my tendency, at home, to fold my neck back under my shell and disappear psychically whenever there is a whiff of atmospheric change. That is what my father did and that’s what I did when I was a kid.

When I was growing up, everyone else’s emotions were so vivid, and they took up so much space that, even in a large Victorian eight-bedroomed house, I felt there was no space for me. There were, however, a couple of spots where I felt calm and protected: One was my room and one was the end of the long farmhouse table where my father sketched and etched endlessly. In that spot, we would sometimes talk about the French novel I was studying for my exams, or he might teach me to see the form in a painting, or explain the Golden Section to me. Largely he would be concentrating on his work and, though I was not by any means always the centre of his attention, just in his peripheral vision, somehow I felt safe. we both did. We were being turtles together.

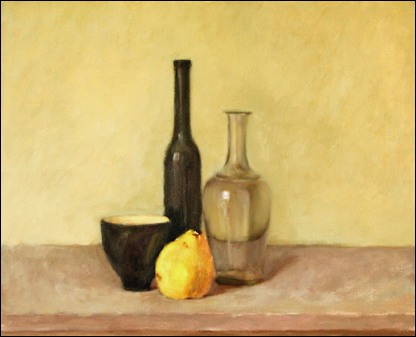

Julian and I sit at the French oak farmhouse table gifted to us for our wedding by my father. It is the end of a working day in Provence. There is a painting hanging upside down on the wall. We are sipping white wine, Julian is making dinner and, freed from our desire for it to resemble the thing it represents, we are looking at the painting’s shapes. It is fascinating seeing the lines; the light and shade created simply by the paint and not by our projection. We discuss it passionately and I am filled with joy that my husband created this thing drawn from objects in our own kitchen – pottery I had picked up in Cornwall or a fruit we had picked together on our morning walk. I love being invited to let my imagination run wild, and that what I see on the square of canvas contributes to the life of this newborn artwork. After an hour or so, Julian decides he will lighten up the right hand corner and thus draw the eye more to the focal point of the shadow. It is time to eat and, a bottle down the line, the pages I have written during the day and wanted to read out loud are still lying on the chair next to me. It is late, we are tired and we both opt for collapsing in front of the telly.

I have just finished a wonderful book by Rohinton Mistry called ‘Family Matters’. In short, Nariman is prevented by his father from marrying the non Parsi woman he loves. His son, Yezad, sees his family’s error and brings up his own with humour, love and sound secular values. Five hundred pages of stunning writing and the tragic consequences of prejudice later, Yezad’s peaceful meditations at the fire temple which help him with the stress of work and family have become full blown religious fanaticism and he is refusing the presence at his son’s birthday party of his non-Parsi girlfriend.

Even if we hang ours upside down, the shapes of our parents’ or grandparents’ relationships are always lurking in the background. Are we merely interpreting the dots on the page? What does it take to paint an entirely fresh canvas, or compose a unique score, I wonder? Or do we have to accept that Mozart and Cezanne, however unique, also emerged from history?